Mangroves protect coastal resilience, for shore, for shore. How do we protect them?

Mangroves make excellent neighbors. As coastal communities experience some of the most stark effects of climate change, mangrove forests do a lot of heavy lifting to keep communities safe and sustainable. As NASA turns the spotlight on oceans this Earth Day, learn how the joint NASA-USAID SERVIR program is using Earth satellites to support these unique ecosystems that protect 15% of the world’s coasts.

Why do mangroves make such good neighbors?

Mangroves do a lot to help communities adapt to climate change. They sequester carbon at a faster rate than inland forests, foster biodiversity by providing habitat and water purification, and protect coastlines from the forces of oceans and extreme climate events. Their intricate root systems trap sediment, keeping coastal waters clean and clear while securing and rebuilding eroded coastlines.

Many mangroves begin filtering freshwater from rivers before it reaches the ocean. This filtration is key for countries like Belize, home to the second largest barrier reef system in the world. The Belize Barrier reef relies on mangroves to reduce the impacts of agricultural runoff, which can kill coral.

Mangroves are a coastline's first line of defense against big waves, high winds, storm surge, and even tsunamis, standing strong against the resulting flooding, soil erosion, and sea level rise. Not only do dense mangrove roots reduce the loss of sediment from waves, they also catch sediment over time, creating a thick mudbank that helps mangroves grow. This ancient mud accumulation and the trees themselves trap and block debris from crashing further inland. The webbed roots can break up the wave force even in severe storms, while the upper tree-limbs act as windbreakers.

Mangrove forests are a pillar of economic livelihoods for many coastal communities. These ecosystems harbor incredible aquatic and vegetation biodiversity commonly used as fishing grounds and foraging sites for shellfish. In Ecuador, shellfish harvesting from mangroves has been a key source of jobs for women in the otherwise male-dominated seafood industry. The clear water, fisheries, and wildlife protected by mangroves also make them key to tourism in countries like Belize and Guyana.

Returning the favor

Mangroves are being removed at a global rate of 1-2% annually, putting coastal communities at greater risk of storms and coastal erosion. Mangroves often occupy valuable waterfront real estate that puts them at high risk of being deforested for urban development or aquaculture. When this happens, the seawalls that are often built to replace them can redirect coastal currents. This means that while seawalls protect one area from waves and erosion, they can make matters worse downshore.

SERVIR collaboratively develops web tools that help partners access satellite information about mangroves to make decisions that help protect these ecosystems.

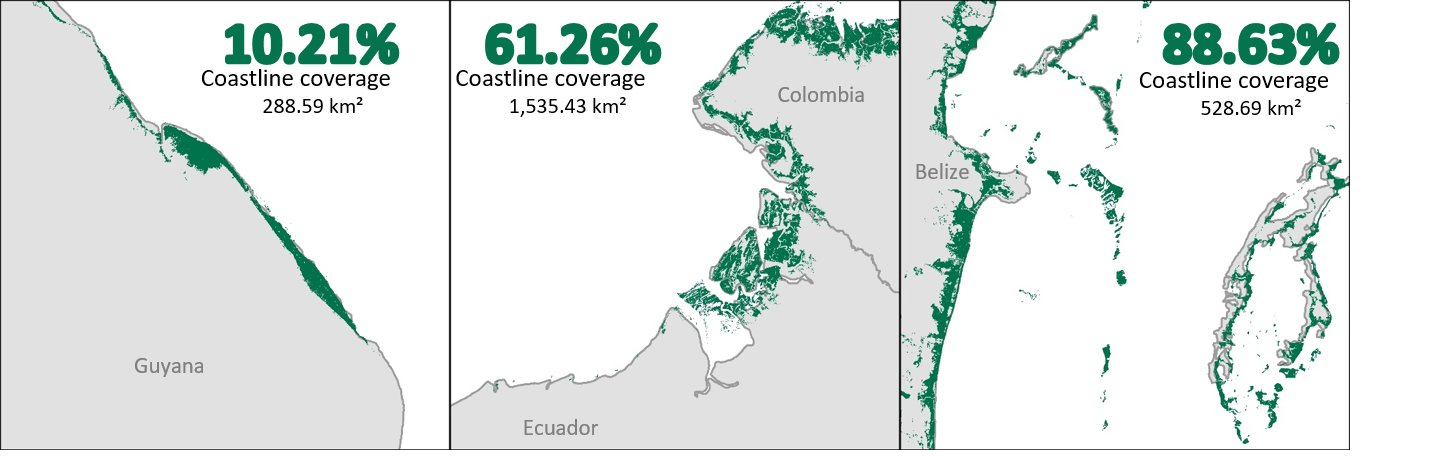

With partners like Guyana’s National Agricultural and Research Extension Institute (NAREI) and Ecuador’s EcoCiencia Foundation, SERVIR’s Amazonia program helps coastal communities use NASA Earth satellites to monitor mangrove loss. Imagery from the Landsat program and other satellites can help scientists spot changes in the extent and health of mangroves over time. Mangrove scientists can also use satellite-based radar to scan for areas where mangroves are thinning or being removed altogether, quickly identifying key areas for remediation and account for changes in carbon storage. SERVIR trains users, like the Belize Forest Department, on how to access this information. Geospatial web tools developed at SERVIR can be used to inform innovative mechanisms like debt-for-nature swaps. The Belize Blue Bond Agreement is a recent example of this mutually beneficial arrangement in action, proposing to protect critical ecosystems by forgiving national debts in exchange for preservation of coastal and marine resources.

The more we learn about the complex and wonderful benefits of mangroves, the clearer it is that this ecosystem cannot easily be replaced by manmade infrastructure. Seawalls along the coast of Guyana are emblazoned with a reminder that earthen barriers cannot replace the benefits of mangrove forests: “Mangroves Protect Us from the Sea. Let Us Protect Them.”

-

Monitoring and Evaluation of Mangroves in Guyana

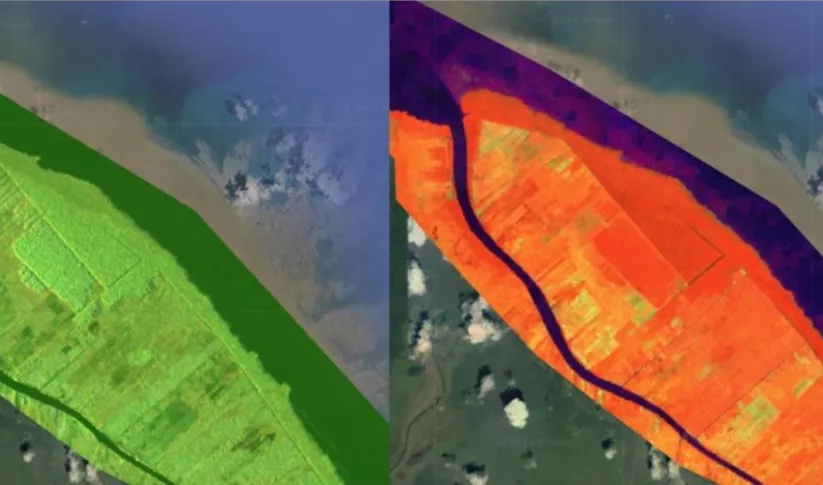

The Monitoring and Evaluation of Mangroves in Guyana service brings Synthetic Aperture Radar (SAR) and other remote sensing resources to map the extent and structure of mangrove forests along the coast of Guyana.

-

Monitoring of Mangroves in Ecuador

The Spatio-temporal monitoring of the mangrove ecosystem, in collaboration with the CIIFEN, generated a Google Earth Engine code to support the monitoring of mangrove change.